GDP and Corporate Growth

None of the four major components of the business cycle, (real income, sales, production and employment) have managed to get back to their 2007 highs, even now as we enter the fifth year of the recovery. This is truly a record, if an unfortunate one.

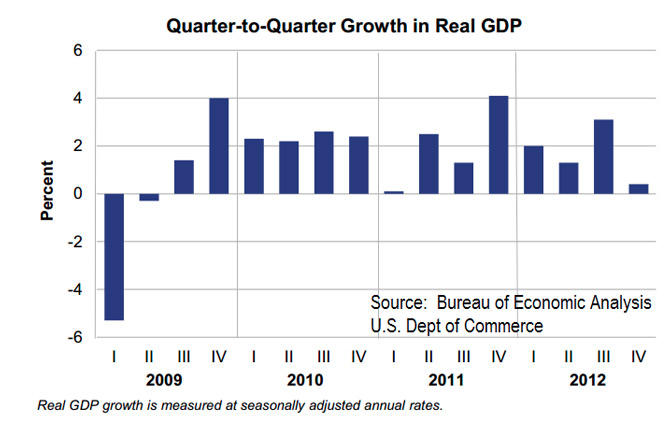

The chart above shows the continual stop and go pattern that has been GDP growth since the financial crisis. Never before in modern history has the U.S. experienced this many post-recession quarters without having at least one back-to-back 3% plus growth in GDP. The first quarter of 2013 was reported on Friday April 26th to have grown by 2.5%, while the second quarter of 2013 is currently forecasted to be below 2%.

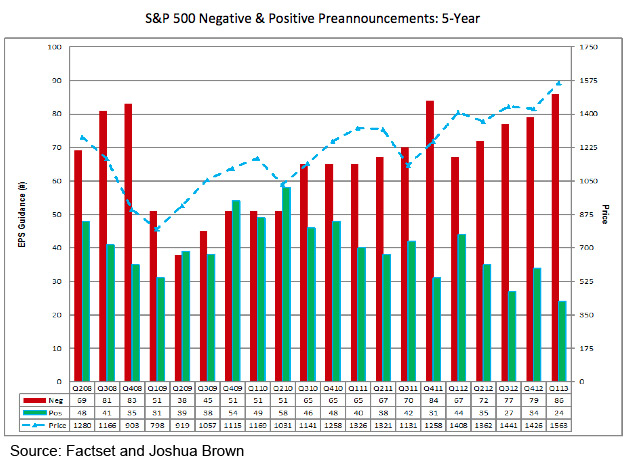

As we head into the first quarter’s earnings season, 78% of companies have issued negative earnings preannouncements, the highest percentage of companies issuing negative earnings guidance since FactSet began tracking the data in Q1 2006.

The chart above shows in red, the percent of negative preannouncements by quarter and in green the percent of positive preannouncements with the S&P in blue. This is a troublesome trend to say the least and has us watching the market movement carefully. Eventually, stock market growth must be supported by corporate earnings growth and the trend for the past 11 quarters has been fewer and fewer positive corporate earnings surprises, as this chart clearly illustrates. The quantitative easing objective of driving up stock prices in order to create a wealth effect that leads to consumers and businesses spending more is not translating into better than expected corporate earnings.