Interest Rates and National Debt

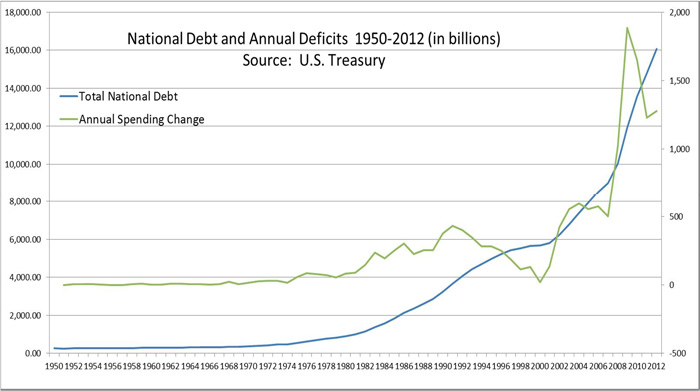

The Federal Reserve has been under considerable pressure to provide details for just how it will control all the excess liquidity that it has created through quantitative easing. The Fed’s balance sheet, which can roughly be thought of as a proxy for the potential money supply, is almost 2.4 times the size it was in 2007. Last month I discussed how excess bank reserves have skyrocketed to nearly $1.7 trillion after having historically averaged near zero since the inception of the Federal Reserve. The Fed has argued that it will be able to slowly raise interest rates and carefully reign in those excess funds to prevent rampant inflation. This is something that has never in history been accomplished, so there is no clear roadmap for how to do this successfully, but for argument’s sake, let’s assume that the Fed is indeed capable. The question then becomes, “How will rising interest rates affect the economy and investing?” One of the largest impacts of rising interest rates will be on the financials of the federal government. The chart above shows the U.S. National Debt from 1950 to 2012 (left hand axis) and the annual deficit/surplus (right hand axis). The current national debt is over $16 trillion. Over the past 5 years, the annual deficit has averaged $1.4 trillion. The national debt as a percent of GDP is almost double what it was in 2007. The annual deficit is 9 times the size it was in 2007. The recent sequester cuts sent D.C. into apoplectic fits with dire warnings of impending doom, however those “cuts”, according to the Congressional Budget Office, represented a decrease in the amount of spending increase that is less than the total increase, which means there will still be an increase in net spending after the sequester, (see Congressional Budget Office “Final Sequestration Report for Fiscal Year 2013” published March 2013). Given the emotional hoopla and doomsday rhetoric, it is reasonable to assume that the current level of deficit spending is unlikely to decrease significantly anytime soon.

The Federal Reserve has been under considerable pressure to provide details for just how it will control all the excess liquidity that it has created through quantitative easing. The Fed’s balance sheet, which can roughly be thought of as a proxy for the potential money supply, is almost 2.4 times the size it was in 2007. Last month I discussed how excess bank reserves have skyrocketed to nearly $1.7 trillion after having historically averaged near zero since the inception of the Federal Reserve. The Fed has argued that it will be able to slowly raise interest rates and carefully reign in those excess funds to prevent rampant inflation. This is something that has never in history been accomplished, so there is no clear roadmap for how to do this successfully, but for argument’s sake, let’s assume that the Fed is indeed capable. The question then becomes, “How will rising interest rates affect the economy and investing?” One of the largest impacts of rising interest rates will be on the financials of the federal government. The chart above shows the U.S. National Debt from 1950 to 2012 (left hand axis) and the annual deficit/surplus (right hand axis). The current national debt is over $16 trillion. Over the past 5 years, the annual deficit has averaged $1.4 trillion. The national debt as a percent of GDP is almost double what it was in 2007. The annual deficit is 9 times the size it was in 2007. The recent sequester cuts sent D.C. into apoplectic fits with dire warnings of impending doom, however those “cuts”, according to the Congressional Budget Office, represented a decrease in the amount of spending increase that is less than the total increase, which means there will still be an increase in net spending after the sequester, (see Congressional Budget Office “Final Sequestration Report for Fiscal Year 2013” published March 2013). Given the emotional hoopla and doomsday rhetoric, it is reasonable to assume that the current level of deficit spending is unlikely to decrease significantly anytime soon.

The current 10 year Treasury interest rate is about 1.8%. It reached its lowest level in July 2012 at 1.53% and the highest rate was 15.32% in September 1981 when Paul Volker put the kibosh on inflation. The historical average rate has been about 4.6%. The current annual interest payment on the debt is just over $220 billion. If interest rates were to rise to only the historical average of 4.6%, that would be an increase of 2.8%, which would be an increase of nearly $110 billion, if we assume for simplicity that all the new issuance is a 10 year terms. (The reality is that some would be shorter term, some would be longer, and this is just meant to give an approximation to illustrate the magnitude of the impact.) That means interest expense on the debt would increase a whopping 50% in the next year. If the deficit spending continued at about the same rate for the next 6 years, annual debt interest payments would become the government’s costliest expense by 2020. For every year that we continue to deficit spend, increasing the national debt, the magnitude of the impact of rising interest rates increases.

That puts the Federal Reserve into quite a pickle if the economy does in fact gets some legs and inflation ignites. Don’t raise rates and face punishing inflation. Raise rates and D.C. is going to be put under even more pressure to reduce spending. No wonder Chairman Ben Bernanke has been giving subtle indications that he isn’t keen on yet another term as Chairman!