Greece in Hotel California

Greece was all over the headlines again last week as the deadline for debt talks neared. The  Maastricht Treaty, which created the European Union, is starting to sound an awful like the Eagles “Hotel California,” with many in Greece left rethinking, “This could be Heaven or this could be Hell.” The treaty provided a lengthy list of requirements to enter the Eurozone “hotel,” but provides no way to exit, making all members, “…just prisoners here, of our own device.” Greece, among quite a few others, didn’t exactly meet the economic fitness requirements to obtain membership in the Eurozone. The current members were well aware that Greece was essentially doping to get the level of performance required and were all too willing to look the other way. After all, “We are programmed to receive. You can check-out any time you like, but you can never leave!”

Maastricht Treaty, which created the European Union, is starting to sound an awful like the Eagles “Hotel California,” with many in Greece left rethinking, “This could be Heaven or this could be Hell.” The treaty provided a lengthy list of requirements to enter the Eurozone “hotel,” but provides no way to exit, making all members, “…just prisoners here, of our own device.” Greece, among quite a few others, didn’t exactly meet the economic fitness requirements to obtain membership in the Eurozone. The current members were well aware that Greece was essentially doping to get the level of performance required and were all too willing to look the other way. After all, “We are programmed to receive. You can check-out any time you like, but you can never leave!”

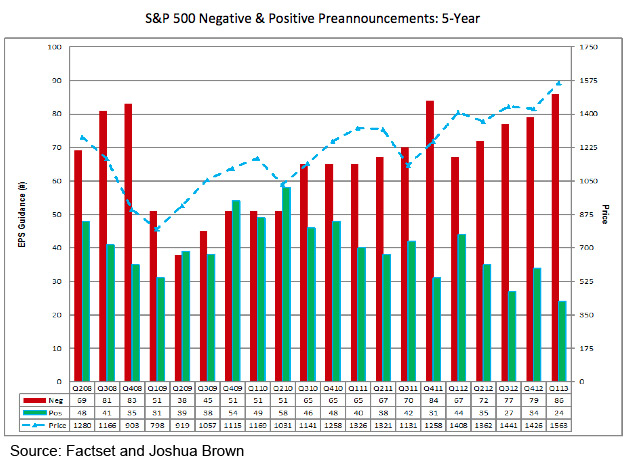

After Greece made it onto the Eurozone team, things went quite well for a while. The global economy appeared to be performing in tip-top shape and “dealers” for Greece’s performance-enhancing creative debt securitizations were ubiquitous. Now before anyone gives into the desire to finger wag, first recall that parts of the US economy also indulged in such performance-enhancing financial supplements, (housing and now the auto sector). Frankly, pre-financial crisis the proliferation of creative debt securitization on the global stage was a lot like an excerpt from a Lance Armstrong post-2012 doping deposition, “Everyone was doing it. You had to if you didn’t want to be left in the dust.” Pssst, a version of this is still going on today, just ask any company that is juicing its EPS by using newly issued debt to fund stock buybacks such as Apple (AAPL), IBM (IBM), Monsanto (MON), CBS (CBS) and many more.

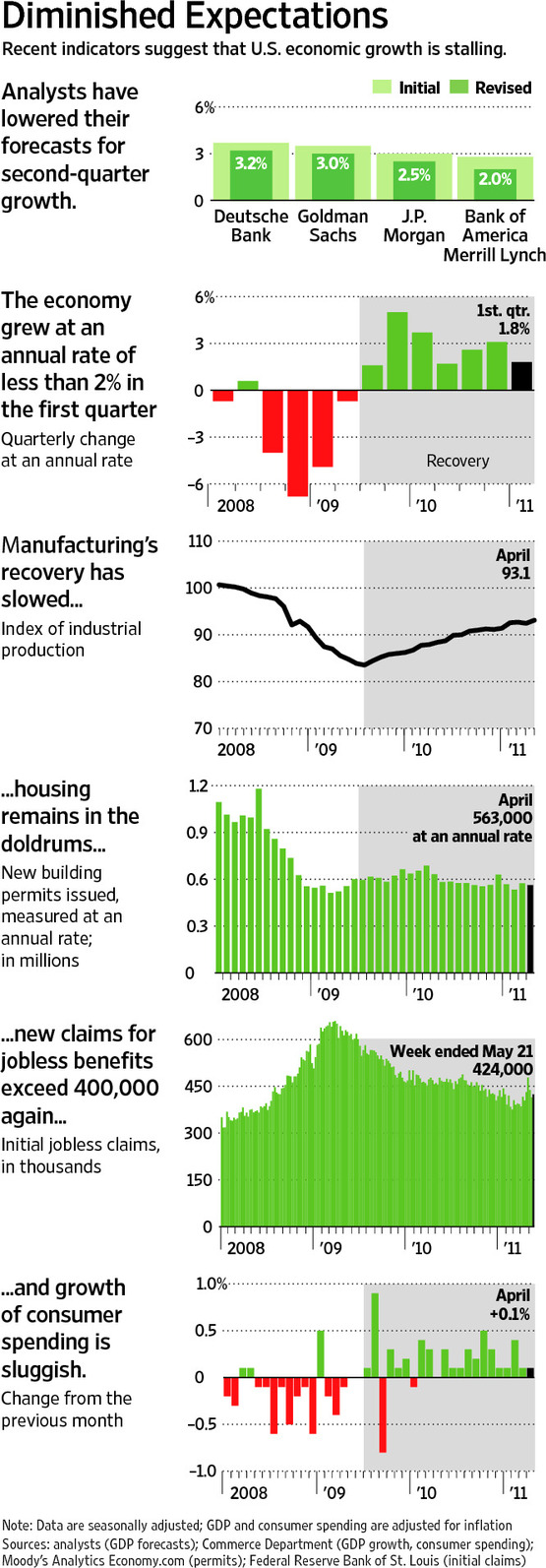

Today, global economic conditions are such that the hills have gotten a hell of a lot steeper, the pavement is full of cracks, there are powerful headwinds, rain flurries and Greece’s pre-crisis performance-enhancing suppliers are no where to be seen. Debt-doping allowed the nation to get away with all kinds of economic sins, gorging itself on regulations and labor laws akin to years of multiple-pint nightly threesomes with my two favorite partners-in-crime, Ben and Jerry, followed by many a lazy day-after spent series-binging on “Ex-wives of Rock” while sprawled on the couch munching on peanut butter Cap’n Crunch out of the box. Now with no “supplements” available, an overweight, out-of-shape and endocrine-exhausted Greece is being told to get pedaling faster and faster on a bike with bald tires, a broken gearbox and gyrating handlebars.

You would think that Germany, of all countries, would remember that driving a nation into the economic ground is never a good idea. Most economists and politicians refer to Germany’s understandable fear of hyperinflation but that overlooks the much more relevant and painful lesson from the impossible demands placed on the country post WWI, which destroyed not only its relationship with its neighbors, but also its democracy and ultimately led to WWII. How ironic that the Maastricht Treaty, which was conceived in part to prevent another war between European neighbors, is now the cause of so much inter-European strife!

Greece simply cannot pay its debt, which is pretty much its standard operating procedure. According to Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart, “from 1800 to 2008, Greece was in default 50.6% of the time,” so angry bondholders, how about a reality check? Last week we mentioned that the nation’s economy had contracted by 26% from 2008-2013, yet it is still managing to remain current on its debt payments while running a primary surplus of about 1.5%. That would be a seriously crowd-pleasing performance on NBC’s The Biggest Loser! The problem is its creditors want Greece to increase that surplus, meaning ride even faster up that blasted hill! Even Jillian Michaels wouldn’t push that hard.

Last Thursday Greece formally requested a 6 month extension after four weeks of brinkmanship, which was quickly returned with an “I don’t think so,” from Germany. On Friday night a four month interim pact was reached that will once again kick the can down the road, albeit a much shorter road than after previous kerfuffles, conditional on Greece submitting a list of reforms by Monday 23rd. Greece submitted such a list close to midnight on Monday, which the eurozone commission officials claim contains significant changes from “a more vague outline originally discussed at the weekend.” One official reportedly said, “We are notably encouraged by the strong commitment to combat tax evasion and corruption.”

The Eurozone finance ministers will hold a conference call on Tuesday to determine the acceptability of Greece’s proposed reform plans. Most likely an agreement will be reached. The bailout money will continue to come and the European Central bank will continue to stand behind the nation’s banking system. However, all the finger pointing and accusatory language has greatly damaged relationships and backed both parties into difficult corners. The next round of talks in four months could be even more contentious.