Michael Jordan and the B-Ball Inequality

I know that this may come as a surprise to many of my regular readers, but I have a confession to make. Michael Jordan is a better basketball player than I. This basketball skill spread needs to be addressed. He shouldn’t be that much better than I. It isn’t fair. No matter how much I practice, no matter what coaching I get, no matter how hard I train in the gym and follow a strictly regimented diet, he will always be better than I. Unfortunately for Mike, the only way to address this issue, (given that there is a clear cap to my potential at 5’8″ with a proportional wingspan and at best, only slightly better than average springs) is to handicap him. Now wouldn’t the world be a better place if the difference in our abilities were materially reduced?

I know that this may come as a surprise to many of my regular readers, but I have a confession to make. Michael Jordan is a better basketball player than I. This basketball skill spread needs to be addressed. He shouldn’t be that much better than I. It isn’t fair. No matter how much I practice, no matter what coaching I get, no matter how hard I train in the gym and follow a strictly regimented diet, he will always be better than I. Unfortunately for Mike, the only way to address this issue, (given that there is a clear cap to my potential at 5’8″ with a proportional wingspan and at best, only slightly better than average springs) is to handicap him. Now wouldn’t the world be a better place if the difference in our abilities were materially reduced?

You probably get where I’m going with this. Before anyone gets into a tizzy and starts making all kinds of accusations about how mean and uncaring I am. There is a serious problem today with respect to income, but the problem, thus the cure, isn’t what is preached in the popular media.

The billionaires at Davos, in what can only be described as irony of epic proportions, all agreed that “Severe income inequality” is one of the top 10 global risks of greatest concern for 2014. You can read the report here.

So let’s break this problem down. When people talk about income inequality there is a knee-jerk assumption that by definition, income inequality is bad, which in reality is quite destructive to society as a whole. It intuitively doesn’t make sense that as a society we should strive to have income equality where regardless of what value an individual generates, income ought to be equal. The guy who chooses to work 3 days a week sweeping floors at the local Walmart clearly should not enjoy the same income as Steve Jobs! So some degree of income inequality is Ok, right? But not too much? Hmmm, ok, then how much? Who gets to decide how much is too much and how do they make that determination? Then how do they enforce it? How do we trust that the person we give such enormous power to won’t abuse that power? For argument’s sake let’s say they don’t. What about their successor? How likely is it that we continue to have only angelic geniuses that are able to manipulate society into a Utopian income spread without ever falling prey to corruption and graft? So far the record throughout history doesn’t lead one to believe that is it all likely.

I spend a great deal of my time in Italy, where I sadly witness first-hand the awful consequences of this sort of societal structure. If I get paid roughly the same amount whether I work my tail off and take risks trying to improve my performance or if I put in essentially the bare minimum level of effort, why try? I see this everywhere. Incredibly bright people who could be innovating like crazy, coming up with all kinds of solutions that would benefit their companies and eventually their nation are beaten down by a system that provides no incentive for those who really try to do something great. Those who are naturally innovators want desperately to try new things, take risks, but for them there is only downside risk. They can’t improve their income level through hard work and risk taking. They only risk annoying their colleagues and supervisors by trying to improve things. Status quo is the rational choice. Notice the level of innovation coming out of Italy and its rate of growth!?

I sit at dinner and hear the agony in my friend’s voices as they vent their frustrations and their anger at how a colleague who does very little gets paid roughly the same as they do. This type of structure infects relationships because it forces people to live in a lie, a lie which is painfully obvious to everyone. The guy who barely shows up to the office and only does the bare minimum knows that the guy who’s working his tail off, (he can’t help but try as innovation is in his DNA) is angry that they both get paid roughly the same. They both are aware of the resentments, but are powerless to do anything about it because society tells them that this is a far better way to live. It is more fair. What the hell? More fair that those who are willing to sacrifice and take risks are basically barred from enjoying any benefit from doing so? My Italian friends all talk wistfully about how great it would be to work in the U.S. where at least there they can hope to get rewarded for accomplishing something great.

As for the U.S., I struggle to see where this horrific trend we keep hearing about is evidenced. The table below is from an excellent study by Alan Reynolds of the Cato Institute. You can read the entire report here.  The data does not prove out the claims, at least in the U.S.. The bottom two quartiles and the top quartile enjoyed nearly the same increase in income on a percentage basis from 1989 – 2007. From 2007 – 2010, the bottom quartile experienced a rise in income, while all others experienced a decline.

The data does not prove out the claims, at least in the U.S.. The bottom two quartiles and the top quartile enjoyed nearly the same increase in income on a percentage basis from 1989 – 2007. From 2007 – 2010, the bottom quartile experienced a rise in income, while all others experienced a decline.

Now where is inequality a problem? Barriers and disincentives to improve one’s lot in life ARE problems. Subsidies such as those in the Affordable Care Act put the poor in a veritable poverty trap in that as they work to improve their situation, the subsidies are taken away at such a pace as to make them far better off overall working less. That is both demeaning to the individual and immoral in that it forces others to eternally be enslaved to subsidize their fellow citizen, despite the reality that the guy being subsidized may desperately want to get out of his situation, but is faced with overwhelming incentives that keep him dependent, resentful and demoralized.

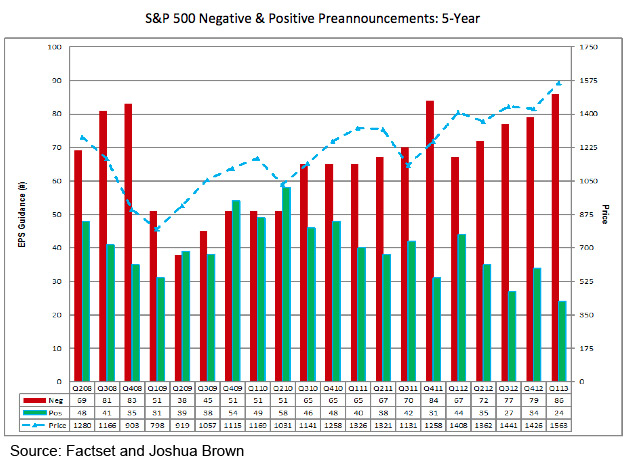

There is also something horribly wrong with a system in which savers are punished through financial repression. The Federal Reserve, by keeping interest rates low, forces savers to go into inappropriately risky investments just to try and get a reasonable return. Those who are already wealthy and are able to invest heavily in the stock market enjoy out-sized returns courtesy of the Fed’s QEInfinity as evidenced by the 90% correlation between the Fed’s balance sheet and the stock market starting in 2008. Previously the correlation was essentially 0!

The free market system is far from perfect, full of all kinds of flaws, but it is infinitely better than anything else out there. There are no angelic, omniscient bureaucrats that can manipulate our world into a more Utopian state. Be wary of any who claim they can.