Friday’s January Job Report a Blowout, But There’s More You Need to Know

This morning’s January Employment Report showed the economy added 227K jobs in January, beating consensus expectations for 170K jobs. This comes after the surge in January private sector jobs to 246K vs. the expected 165K reported by ADP earlier this week. Great to see some data to back up the uber-optimistic market these days, but there is a bit more to this story.

While the headline number looked great, digging beneath the headline and into the details the report wasn’t as rosy. If we take into account that revisions to the prior two months reduced jobs by 39k, the average is closer to expectations and the 3 month moving average is less impressive.

We also saw a decline in employment in the key working age group of 25-54-year-olds of 305k, which was partially offset by a 195k increase in 55+ employment – more near retirement working and fewer in prime working years isn’t a positive sign. Looking at the bigger picture, job growth averaged 239k in 2014, falling to 213k in 2015 and this report brings the recent 12-month average to 182k. The pace of job growth continues to slow, total payrolls rose now up 1.6 percent year over year versus 1.9 percent in the first quarter of 2016, which is typical with an economic recovery that is rather long in the tooth.

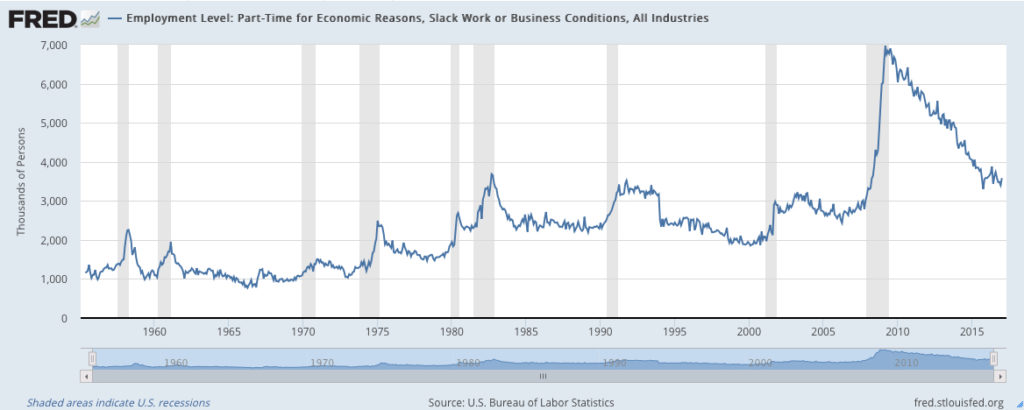

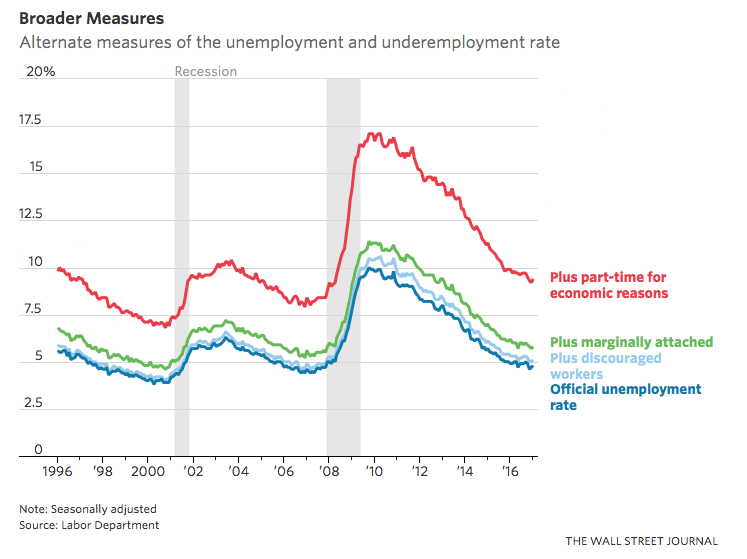

We also saw an increase in those working part-time because they cannot find full-time work by 232k – we’d obviously prefer to see that decline. Those expecting a Fed rate hike soon should note that this is one of Fed Chair Yellen’s favorite metrics.

Along these lines, we saw the underemployment rate (as measured by the U6) rise to a three-month high of 9.4 percent from December’s 9.2 percent.

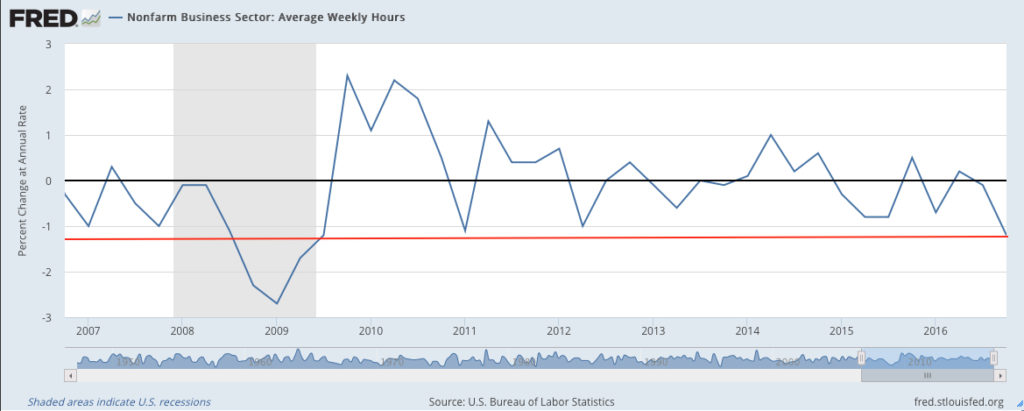

Along with that increase in part-time workers, we saw the change in weekly hours worked drop to a rate not seen since the recession, which indicates that future strong job growth is less likely.

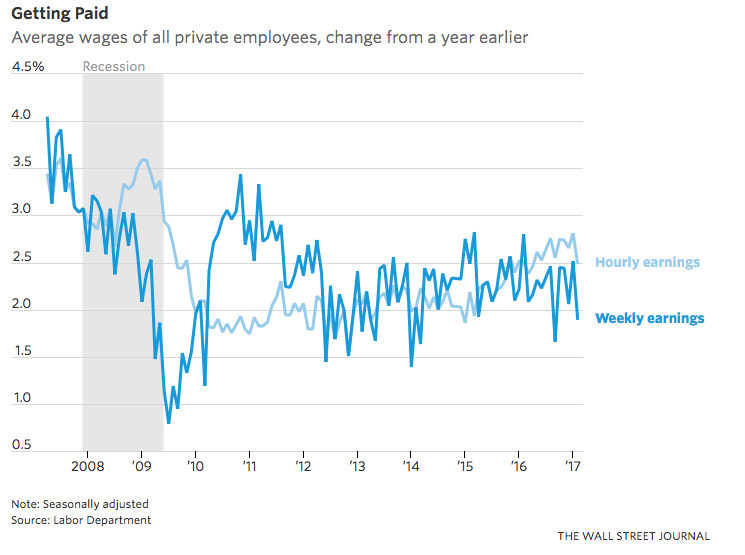

More frustrating is the lack of meaningful wage growth, rising just 0.1 percent month over month and 2.5 percent year over year, the weakest year over year gain since last March. Average weekly earnings saw the weakest gain in six months at 1.9 percent.

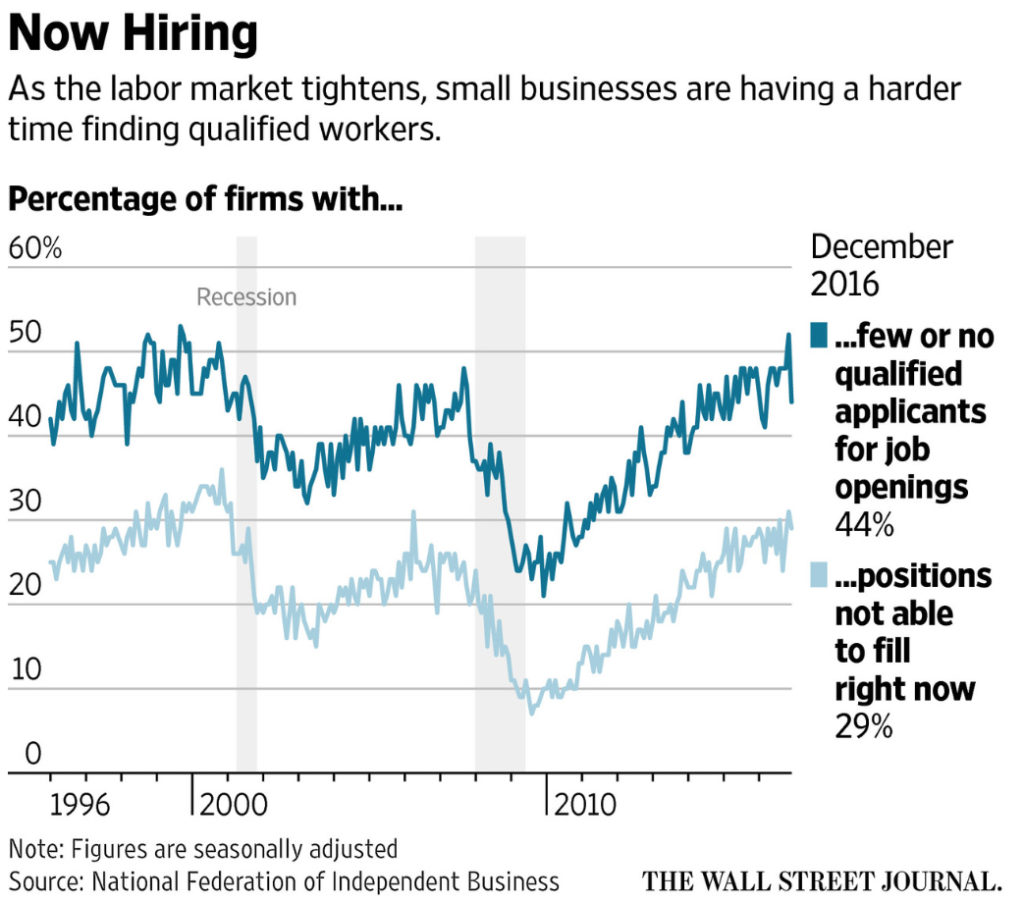

One of the biggest challenges facing the employment situation is the mismatch between available labor and business needs. Small businesses are finding it increasingly more difficult to find qualified talent for the position they are looking to fill, which clearly negatively impacts their ability to grow – another headwind to the economy. This is also reflected in the record level spread between job openings and hirings we see every month in the JOLTS report. Our next take on that data comes next week with the December report.

All this those doesn’t address the much bigger issue the country is facing and this is what investors need to understand far more than the monthly fluctuations.

The growth of an economy is dependent on just two things: the size of the available workforce and productivity levels. For an economy to grow one or ideally both of those need to be rising.

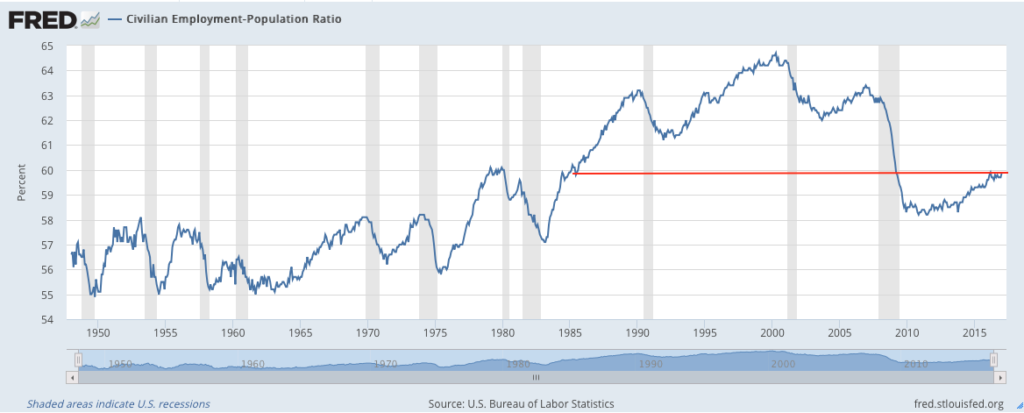

It has become a popular refrain to refer to President Trump as the next Ronald Reagan, implying that his policies will lead to the type of economic boom that the country experience during and after Reagan’s presidency. We’d love nothing more than for the country to see that kind of growth again, but the fundamentals today are very different from those in the 1980s.

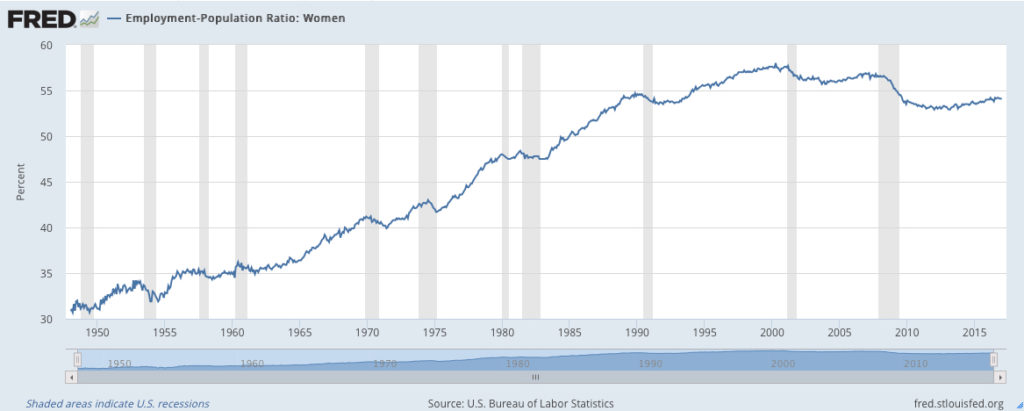

When Reagan took office median baby boomers were moving into their prime working age and the percent of women in the workforce was rising significantly.

When Reagan took office, less than 50 percent of women were employed. That number peaked in 2000 at 58 percent but has declined to just 54.1 percent in January.

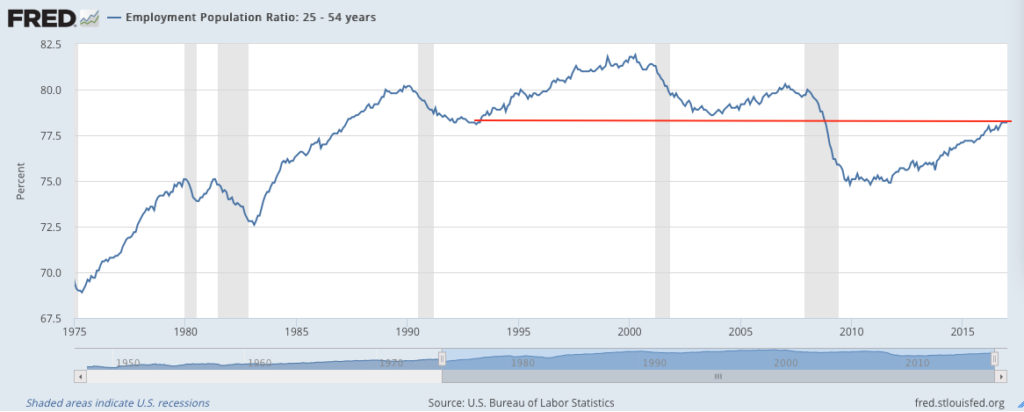

The weak employment relative to total population though isn’t all about the baby boomers retiring as the percent of those in the prime working age cohort ages 25 to 54 years rose dramatically from the early 1980s to just over 72 percent to a peak of over 81 percent in 2000. As of January, 78.2 percent are employed, a level we haven’t seen, outside of a recession, since the late 1980s.

You might have heard as well that fertility rates in developed economies have been slowing dramatically. In many European nations the rate has dropped below replacement levels, which means that without immigration, the total population of those countries would be declining. In the U.S. the rate of growth of the working population, either through immigration or native births has been slowing significantly.

The potential growth rate of the U.S. economy is materially different today than during Reagan’s era because of significant changes in the dynamics of the labor pool. Today the percent of people choosing to be in the workforce is lower than it has been in decades. Compounding this problem, the growth rate in the working age population has slowed dramatically from where it was in the 1980s.

To increase the potential growth rate for the economy, outside of any handicaps placed on it through legislation, regulation or taxation, the population of those in the workforce needs to increase and/or productivity needs to rise.

When it comes to productivity, it is all about capital investment and for years we’ve seen companies choosing to buy back shares rather than reinvest in their own productive capacity… but that’s a topic for next time!